Instruction in Iraq: A story of schools

By Adhid Miri, Phd

Schools tell us a great deal about our history. Within them, we celebrate memories, principals, teachers, students, parents, friends, uniforms, events, and the building itself.

Once upon a time, Iraq had a well-functioning British-style education system, consisting of primary and secondary schools and eight tertiary institutions, including a well-regarded medical school in Baghdad and one of the oldest Islamic universities on Earth, Mustansiriya University, dating from the year 1233. Seriously damaged during military occupations and by rioting students in 2007, the university suffered trauma from which it is still recovering.

In the 1970s, Iraq had one of the finest education systems in the world, approaching 100% literacy; however, a sequence of wars and sanctions left it severely damaged. Since 2003, 84% of the infrastructure in Iraqi higher education institutions have been burnt, looted, or damaged in some form.

War, political instability, deteriorating safety conditions, and a lack of high-quality study options in Iraq have been student challenges over the past decades. Assassinations and the ongoing militia threats have affected hundreds of Iraqi teachers and academics and represent the sad situation in Iraq.

There is also conflict between fundamentalist religion and the concept of free and open education for all. While this continues, children suffer. The situation is particularly depressing among primary school-age girls in poor areas.

Iraq’s educational system is in ruins and in need of reconstruction. Among the many challenges facing the citizens are the creation of a new education system.

History

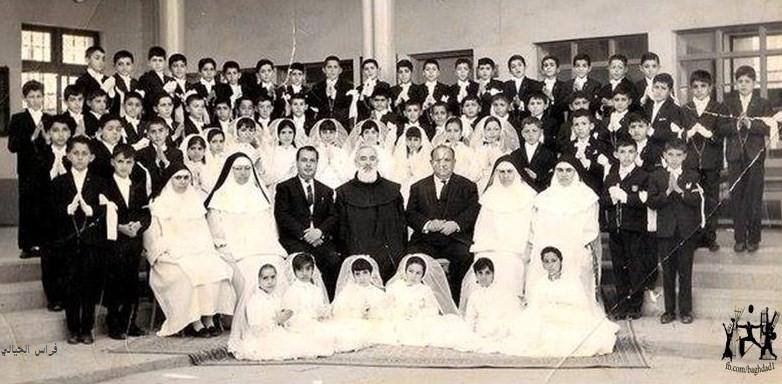

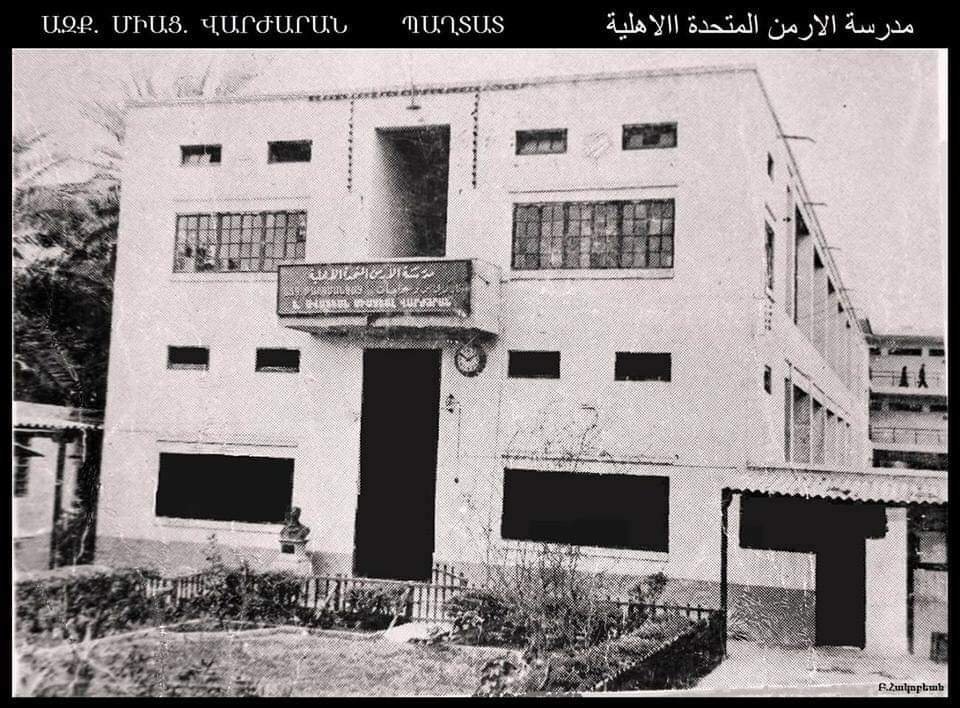

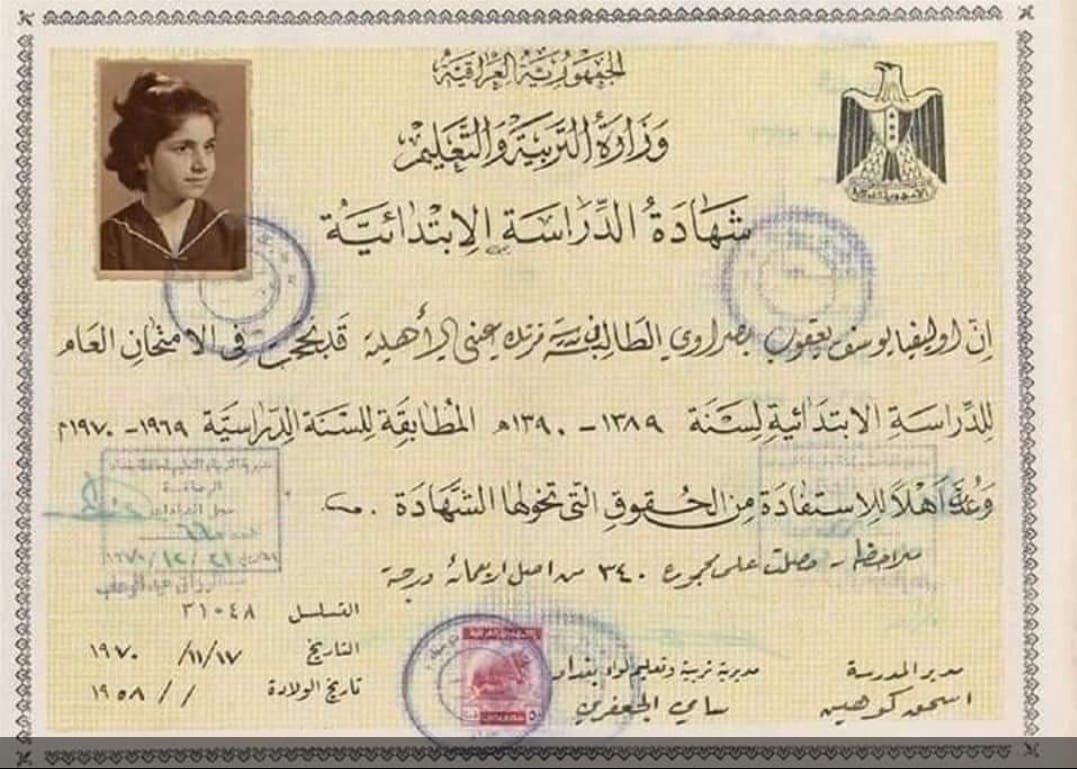

During the royal period of Iraqi history, education led to significant developments and new horizons opened in terms of primary, secondary, and preparatory schools, female schools, Jewish schools, Christian schools, private as well as foreign schools, and special schools for craftsmanship.

The Carmelite Catholic Mission was active in Baghdad in the early eighteenth century, and they established a small religious school attached to the Latin Church in 1721. Its founder was the French priest, Emmanuel Baillet.

The school taught the principles of reading and writing along with morals, discipline, religious education, and church rites. It eventually separated from the church, and in 1737, began working according to “modern” European education systems under the name Saint Joseph School. It introduced to the school curriculum modern sciences and the languages Arabic, French and a little Turkish.

In 1859, it became St. Joseph High School. It had 20% non-Christian students — children from affluent families who enrolled to learn English and French. The Iraqi government seized the school when nationalizing private schools after the Baath coup in 1968 and the name was changed to Al-Makasib School.

The Ottomans rulers of Iraq gave Christian and Jews a freedom to start private schools if they were supervised by the local education management authority. Between 1805 and 1879, there were 24 Christian schools throughout Iraq.

In 1850, two Jesuits were sent from Beirut to Baghdad to determine if the time was right for a Jesuit mission there. Their caravan was robbed on the way to and from Baghdad; consequently, they decided that the time for a mission there had not yet arrived.

Considered one of the earliest Jewish schools in Iraq, The Alliance was founded in 1864 and funded by Barron Rothchild. Its student body was made of Muslim, Christian, and Jewish youth, and classes focused on teaching Jewish religious texts with specific focus on the Talmud and the Torah. It taught English and French as secondary languages in addition to Arabic, Hebrew, history, geography, sciences, chemistry, and biology. In the first semester of its first year (1864-1865) it had 43 students; by midterm the number jumped to 75.

In 1873, the first batch of the French Dominican Sisters of the Presentation came to the city of Mosul and opened an elementary school for girls. In 1880, they came to Baghdad and founded the first monastery in the old Christian district neighborhood, Aqd al-Nasara. They opened the Central School, then another school in the eastern gate (Bab Al-Shargey) area, and another in the eastern Karrada (Karrada Al-Sharqiya).

In addition, the establishment and twenty-year operation of a school for Jewish girls in Ottoman Baghdad at the turn of the twentieth century was an amazing adventure. The fact adds depth and texture to our understanding of the modernizing transformation in education that took place on a global scale between 1890 and 1930 in Iraq.

In 1920, the Chaldean community opened Al-Tahira (“The Immaculate”) school for boys in Baghdad. Christian schools’ buildings were usually attached to one of the old churches.

In 1924, an adventurous young couple accepted a commission to open an American school for boys in Baghdad. Setting foot on Iraqi soil the very day that the Constituent Assembly convened in Baghdad to frame a constitution for the new nation, Ida Staudt and her husband Calvin witnessed the birth of this fledgling country.

For the next twenty-three years, they taught hundreds of young boys whose ethnicity, religious background, and economic status were as varied as the region itself. Cultivating strong bonds with their students and their families, the Staudts were welcomed into their lives and homes, ranging from the royal palace to refugee huts and Bedouin tents.

The School of the Presentation Sisters in the heart of Baghdad’s Tahrir Square (Eastern Gate) was established in 1925 when King Faisal I donated a piece of land to a group of French nuns in exchange for their efforts in combating the plague that was spreading in Baghdad. It was called Progressive Sisters School until 1964 when the government nationalized the private schools and changed the name of the school to Al-Aqidah Secondary School for Girls.

The Shamash Jewish High School in Baghdad, an all-boys school, was founded in 1928. It was like an oasis in the desert; it was funded by the Shamash family of Manchester, England who donated the building and with it 17 stores, a pharmacy, and a guest house/hotel for travelers. The curriculum included Turkish and other foreign languages with an emphasis on English. It was governed by its own committee which was headed by Shlomo Saleh Shamash.

In the beginning, this school was also an elementary and middle school but in 1942, the elementary classes concluded and in 1949 the middle school closed. The students transferred to Frank Iny School, leaving only the high school.

Although many Jewish schools had once operated in Iraq, often with the support of the local Jewish community, Iraqi government, or international Jewish organizations in Paris and London, these schools began to close in the 1940s. The Frank Iny School was the last Jewish school in Baghdad, but eventually closed in 1973 as most of the remaining Jews fled the country.

Baghdad College

In 1932, the same year that Iraq gained its independence, four Jesuits from the United States arrived in Baghdad and established Baghdad College High School. During its first two years, the school rented two houses in the center of Baghdad near the river. Not particularly well-constructed, the classroom floors were of rough, uneven brick. One historical description labeled it “too small, the light not so good, windows and doors were ill fitting and when a dust storm came up, the atmosphere was not pleasant.”

In its first year, 375 boys applied and 120 were accepted, dropping to 107 by the year’s end. Students ranged from 13 to 20 years old; the average student was about 15. In the beginning, there were nine faculty for the 107 students, including four Jesuits and five Iraqis. Over the years, Baghdad College grew to include over 1,000 students and a faculty of 33 Jesuits and 31 Iraqi laymen. The growth was not easy or painless. The centuries of antagonism between Islam and Christianity and the long hostility between East and West left scars on the Iraqis.

From the early days, Baghdad College followed Iraqi school programs and the Jesuits avoided bringing American curriculum to Iraq. They did offer their students a distinct advantage – bilingualism in Arabic and English. For many students, this was the first time they saw real blackboards, history maps, hygiene charts, projectors, movie machines, and individual armchair seats. In the eyes of their Jesuit teachers, the boys completely won their hearts.

Students learned science and mathematics in English and Arabic. They were prepared to take the final government exams in Arabic and to pursue further scientific study at Baghdad University in English. Several were judged competent by the government to study abroad in the U.S. and Great Britain.

During the four decades following independence, both the Jesuit mission and the country matured. In just 37 years, Iraq’s population expanded from 3.5 million to 8.5 million while the Jesuit population grew from four to 61. Iraq’s secondary school grew in enrollment from 2,076 Iraqi students in three schools to 270,000 in 840 schools while the enrollment in the Jesuit schools increased from 120 students in a few rented houses to 1,100 students in nine buildings at Baghdad College.

In 1952, a university named Al-Hikma (“wisdom”) was established by the Jesuits.

Revolution

Iraq’s public and private education started shifting after the 1958 coup that overthrew the constitutional, pro-western monarchy. It has been in decline ever since, with competing philosophies about testing and methods falling in and out of favor. Meanwhile, the Jesuit education of 1932-1958 and during the turbulent years 1959-1968 maintained its consistent stance based on faith and integrity, educational rigor, and character building.

The revolution of 1958 and each succeeding revolution was a crisis of sorts. For a time, it seemed that the Jesuits would weather this crisis as they had previously. School and work went on for another year until a new revolution brought to power a socialist government more interested in controlling all private education.

The government decreed that it would administer AI-Hikma while the Jesuits continued to teach. The Jesuits accepted the proposal and attempted to work in the new framework for a few months until an extremist element in the government decreed their expulsion from Iraq in November 1968. A year later the American Jesuits at Baghdad College were ordered to leave by the same group.

Current Status

Education in Iraq is highly centralized, and state controlled. The state fully finances all aspects of public education such as supplying books, teaching aids and free student residences.

Arabic is used as the primary language of instruction at all institutions, although Kurdish is taught in Kurdish areas. Pre-school education lasts for a duration of two years and is open to children at four years old; primary education is six years in duration and is compulsory through age 11. Secondary education in Iraq is six years in duration and completed in two stages: Intermediate and Preparatory.

Even though it is now gone, ISIS damaged the Iraqi education system severely. One out of every five schools in Iraq were put out of use. The terrorist group really hurt the country’s education, by closing some schools and using others as a place to radicalize children. Parents were forced to send their children to these schools under the threat of death.

Even after ISIS was expelled, many children were out of school for two years, because of the closure of many schools. This meant the loss of two school years and the need to catch up educationally.

Unfortunately, the Iraqi government does not dedicate enough budget for the education of the country’s youth. Most of the Iraqi government’s budget is spent on religious institutions and the military.

Even if the situation is quite dire when it comes to education in Iraq, international organizations have not left the country without help. For example, UNICEF has made tons of improvements, building new schools and fixing existing water systems in addition to training more than 50,000 teachers and supplying children with school materials. UNICEF has helped around nearly 700,000 children access education in Iraq.

U.N. statistics indicate that the average Iraqi boy over 15 has less than 5 years of schooling and nearly half of Iraqi girls have none. Bombing, looting, and burning (including the education ministry headquarters) in 2003 administered the coup de grace to the old system—and created a golden opportunity to build a new one.

The fight for education is far from over in Iraq, and children continue to search for glimmers of hope. Children’s education is key to the rebuilding of society in Iraq and mandatory for the troubled nation to achieve a sustainable peace.

Educating children is the best hope for the future of Iraq. Let’s hope that this will happen in the years to come.

Sources: Christians in Iraq by Saad Salloum, Jews of Iraq by Yacoub Yousif Goriya, A journey in the History of Iraqi Jews by Yousif Rizq Alla Ghanima, Articles by: Jonathan Sciarcon, Dr. Aziz Asaad, Karam Jasim Mohammed, Ukrainian National University, Jassim Mohammed Rajab, Fadi Salam Iliya, CRS, Majid Khadduri, Billy Briggs, UNICEF.